The more things change, the more they stay the same.

If you were to ask dairy farmer David Conant, he’d likely tell you there’s a lot of truth in that old adage.

He comes from a long line of Conants who have farmed more than 500 acres of sandy loam soil along the banks of the Winooski River in Richmond.

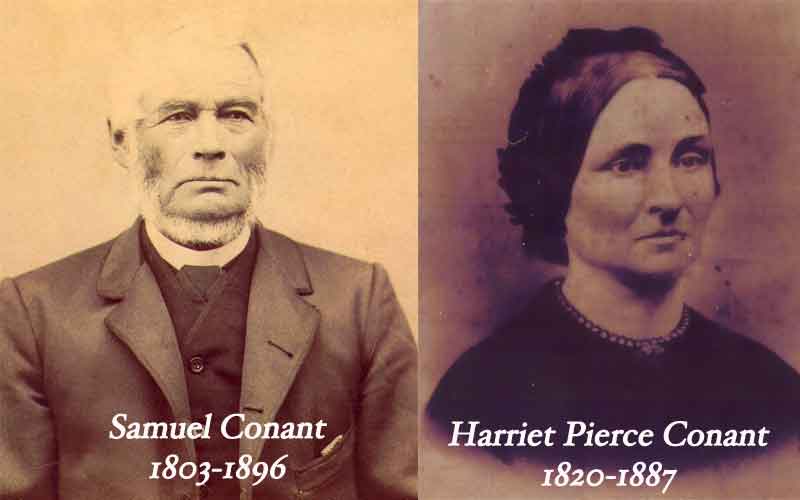

The family’s farm at this site dates back to 1846, when Samuel Conant and Harriet Pierce Conant had the good foresight to move their existing stony farm to what was then known as “the turnpike farm.”

Since then, five more generations of Conants have cultivated the land.

And it is David’s sincerest wish that his and his son Ransom’s generations are far from being the last.

“This is my legacy, and I am very conscious of that,” he says. “One of the things you can do to have a better life is to leave the earth better than you found it, whether you grow a single rose or a thousand acres.”

Ensuring that many more Conants to come may know the blessing of farming this healthy, verdant land has required David to get comfortable with something that makes him uncomfortable.

“I’ve done this for so long, I have a hard time changing my ways,” David explains. “My son once told me, ‘Dad, this isn’t your grandfather’s farm anymore.”

When we visited with him on a bright October morning to learn more about his family’s efforts to be innovative farmers and good stewards of the environment, it quickly became apparent David has embraced change a bit better than he lets on.

He, his son, and their employees had recently finished harvesting corn and injecting manure on all 400 acres of corn land. Manure injection is a process of applying fertilizer just below the surface that reduces nitrogen and phosphorus run-off.

“Our manure pit is pretty much empty right now,” David tells us, “and we keep it that way in case of an extreme weather event, so it doesn’t overflow.”

The Conants had also begun planting cover crops on all of their cropland. Cover crops help fields hang onto their soil and nutrients during Vermont’s harsh winters and rainy springs. On 100-150 acres of the cropland, the Conants are double-cropping rye and triticale, a hybrid of wheat and rye that has a higher yield and forage quality.

Meanwhile, David and Ransom were patiently waiting to resume their fourth and fifth cuts of hay following a couple days of precipitation. While wet hay leads to mold, decay, and even combustion, driving equipment on wet fields is not ideal, either. That contributes to soil compaction, which results in reduced rates of water drainage and filtration, and makes it difficult for seeds to germinate.

David and his family are certain not to take the health of their soil for granted.

“We are truly blessed to have the cropland we do,” he says, “When it’s really dry, like this summer, our soil holds moisture quite well. And when it’s really wet, we can handle the water.”

The water not only comes from rain events–which have grown more significant in recent years due to climate change–but also from the Winooski River, which runs through the farm.

“We are concerned about the river and its health. We think about it every day,” David shares. “We manage our soils and our nutrients to protect the river. That’s one of the biggest challenges we have.”

Perhaps the largest project the Conants have undertaken to protect water quality and soil health at their farm is their manure management system.

Ten years ago, they presented a plan to the Vermont Agency of Agriculture, Food & Markets (VAAFM) and the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) to build a manure pit, establish transfer lines for a dragline system, and install a pipe under the river to pump manure to another large parcel of their farm.

Initially, they received a lot of support from VAAFM and NRCS for the first two phases of the project, but the third phase required more learning and understanding.

“Everybody had to educate themselves about how effective and safe the pipe would be,” David explains. “It took about three years to do our research, then we all understood how important the project could be.”

The Conants are very appreciative of VAAFM and NRCS’ support.

“Without their engineering expertise, financial support, and the people who’ve taken an interest in what we want to do, we wouldn’t be where we are today,” David says. “It has allowed us to manage our manure and nutrients better.”

David also attributes their success to their active participation in the Champlain Valley Farmer Coalition. He was a founding member of the group 10 years ago and continues to serve on the board to this day.

“As a group of farmers, we are so much more aware of the issues we face and how they’re looked upon by the general public and state agencies,” David says. “It has allowed us that contact and ability to be informed.”

Based on his own experience, David encourages other farmers who want to adopt more innovative and costly farming practices to do their research. “Get involved. Be informed. If it’s a capital improvement, be aware of the programs out there that will aid you in putting practices in place. There are programs and people who can assist you,” he points out.

And while the future of agriculture in Vermont feels murky, David is nonetheless optimistic. He already can see how decades of changing practices are improving conditions around his farm.

“When I was a kid, no one ever swam in the river,” he says. “You wouldn’t believe what went by!”

And now?

David’s grandchildren and employees swim in the river, at a place they have affectionately nicknamed Playa del Farmin’, a twist on the coastal resort town of Playa del Carmen in Mexico.

“We’ve always said success is measured by a bulk tank full of milk and a barn full of hay. But it’s not that way anymore,” David says. “Things have changed.”

Indeed they have, David. Indeed they have.