Wilcon Farm in North Ferrisburgh, VT has been a member of the Champlain Valley Farmer Coalition since the organization’s founding in 2012. Ben Dykema has served on the Board of Directors since 2013.

“I believe in the future of agriculture…in the promise of better days through better ways, even as the better things we now enjoy have come to us from the struggles of former years. “– The Future Farmers of America Creed

It’s 1967. Ben Dykema is four, and his family’s leased farm in New Jersey suffers a fire. His parents, Cornelius and Wilma, bring their family to North Ferrisburgh, a community of fellow Dutch immigrants, to start over. They milk 50 cows.

It’s 1973. Ben is ten, and his father gives him $100 to buy a calf. By the time Ben graduates from high school in 1981, he has built a herd of 30 cows from that calf’s lineage.

It’s 1983. Ben marries Kris. Five children are on the horizon. A few years into their marriage, they form a partnership with Cornelius and Wilma. Seven years later, Ben and Kris purchase his parents’ real estate, and eventually all of their cows and equipment. Ben is quick to add, “No gifts when you have four other siblings who are not on the farm!”

It’s 1998. Fire rages again. “Everything burned. Gone,” says Ben. “All the original buildings. Lost cows, equipment, garage, shops. Almost the house. Where do we go from here?”

When he, a co-owner of Wilcon Farm in North Ferrisburgh, was up for re-election to the Champlain Valley Farmer Coalition Board of Directors in January 2020, he remarked, “Forty years ago, I memorized the FFA Creed and always find it worth a read and as a reminder for everyone to keep up the good work. If it was only about me and the modern farm generation, we all would have probably done something different.”

Wilcon farm, in its latest form, is still standing. Ben has just finished second cut, the first time in his life that has been done by June 10.

“I believe that to live and work on a good farm, or to be engaged in other agricultural pursuits, is pleasant as well as challenging; for I know the joys and discomforts of agricultural life and hold an inborn fondness for those associations which, even in hours of discouragement, I can not deny.” – The FFA Creed

Many of the farmer members featured in our stories work alongside their family, divvying up chores among parents, siblings, in-laws, and other relatives, according to skill, interest, and need.

Not Ben. Although he owns the farm with his wife, he is responsible for “everything and everything else,” delegating what he can to 12 employees.

While he is a self-described “driven person,” Ben acknowledges that the “drive is dwindling,” and he’s “trying to figure out how to keep the farm running and not be here.”

“My motivation back in the day was, ‘Hey, this is fun,’” he says. “Some days you beat your head against the wall farming, and there’s no reward. But if you can help somebody else, it’s rewarding.”

The immense challenges of an agricultural life are second to Ben’s pride in what he and Kris have built together. “Our efficiency has been great, and that’s why we’re still here,” he explains. “And we do a good job with animals, so I’ve always had cows to sell as an added income.”

He and Kris own a handful of homes surrounding the farm where they welcome visitors on a weekly basis for vacation stays and farm tours.

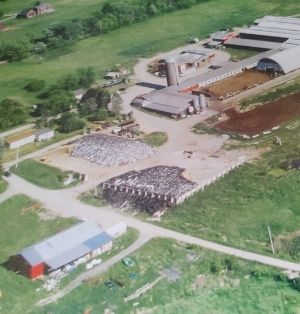

“We try to educate them. It’s a real working farm,” he says as he gestures to the barns, calf hutches, and garages he has built almost entirely by his own hand in a style that favors function over form.

“If I had lots of time and lots of money, I’d do more. But it is what it is. Where do you spend your money in life and what’s your priorities?”

“I believe in leadership from ourselves and respect from others. I believe in my own ability to work efficiently and think clearly, with such knowledge and skill as I can secure, and in the ability of progressive agriculturists to serve our own and the public interest in producing and marketing the product of our toil.” – The FFA Creed

For Ben, one of his top spending priorities is protecting water quality and soil health. Wilcon Farm is situated on 1400 acres across three locations in North Ferrisburgh, New Haven, and Starksboro. In North Ferrisburgh and Starksboro, the farm is part of the Lewis Creek Watershed, while in New Haven it’s Little Otter Creek. At the North Ferrisburgh site, the farm’s manure pit is 100 feet from Lake Champlain’s highest level.

There is a lot at stake. Over the past five to six years, Ben has implemented a number of agricultural practices to support his goal.

He plants no-till corn and cover crops, which, as the name suggests, means that he is able to plant without tilling the ground first. With no-till, farmers, like Ben, are able to keep more nutrients on their fields, reduce soil compaction, and sequester carbon in the soil.

Ben has also implemented a dragline system from a satellite pit for manure injection, a process of applying fertilizer just below the surface that reduces nitrogen and phosphorus run-off. His goal is to “avoid putting manure tankers back on the field…to keep [soil] compaction down.”

But the practice he speaks most highly of is his tile drainage system, a conduit for collecting excess water in the soil. Although not all of his fields yet feature such a system, he installs a bit more every year. He credits tile drainage with helping to reduce and, in some cases eliminate, erosion, washouts, and mud.

“Three years ago, we had four inches of rain, and that field never ran a smidgen off,” Ben observes. “It’s gone with the tile.”

Changing how he farms in order to protect water quality and soil health is both altruistic and practical.

“I always have believed that farmers are the steward of the land, number one,” says Ben. “Who else is going to do it if we don’t do it?”

At the same time, whenever he is considering trying something new, he wonders, “Will it work? Will it work long-term? Will it be profitable? You can only spend money once, and I want to spend it the right way.”

As with all things in agriculture, challenges are abundant. For Ben, one of the biggest obstacles is navigating the ever-changing regulatory landscape. He wants to be proactive and cooperative, but he finds the best practices to be a moving target. It can be taxing, both in terms of time and money, to keep up.

Another challenge is public perception. With 26 homes surrounding 130 acres and numerous tourists to the area, Ben has a lot of curious eyes on his operation and they do not always understand what they are seeing. His tile drainage system, for example, was misunderstood by some to be pop-up sprinklers, or even a means of draining pure manure from his fields. Neither of those are true.

“I’ve got nothing to hide. I try to be neighborly,” says Ben. “I invite people to the farm to help educate them.”

And then there are the economic barriers.

“What plan do you have? Is it an exit strategy plan? Or is it a growth plan? I am on the exit strategy side,” he confesses. As Ben nears retirement with little to no prospect that his children or grandchildren will take up the farm’s reins, he closely considers every dollar he spends and the hundreds of thousands required to invest in state-of-the-art equipment.

“I believe that American agriculture can and will hold true to the best traditions of our national life and that I can exert an influence in my home and community will stand solid for my part in that inspiring task.” – The FFA Creed

Ben credits both the Farmer Coalition and UVM Extension for their support in helping him to be a good steward of the environment. He considers both organizations to be a “great asset,” and enjoys the Coalition’s opportunities to see what other farmers are doing and to learn from them.

If another farmer were to ask him for his advice on water quality and soil health practices, Ben’s altruism and practical nature reappear.

“The economics are a part of it. They work. Not overnight, but they work,” he would say, adding, “Supporting water quality is our responsibility. We can’t do things that used to be okay. You have to change. To change the right way, you have to ask questions, you have to talk to your neighbors and talk to your peers.”

Although Ben’s life as a farmer is approaching the exit ramp, his commitment to the future of agriculture is unwavering.

“I get excited to see younger blood join in, and their enthusiasm for carrying it forward.”

Visit the Future Farmers of America to read their full creed.